27 March 2014

Spotlight on Myanmar

In the lead up to the Mine Ban Treaty’s Third Review Conference in June, ICBL is shining the spotlight on some key countries impacted by the scourge of antipersonnel landmines. This 'Spotlight on Myanmar' looks at issues such as landmine use and production in Myanmar, efforts being made to address the issue, clear contaminated land and provide assistance to victims, as well as the establishment and role of civil society.

The Mine Ban Treaty’s Third Review Conference will take place from 23 to 27 June 2014 in Maputo, Mozambique, 15 years after the treaty’s entry into force.

The ICBL is calling on the mine ban community to take up the Completion Challenge – to ensure that the work started several years ago is actually completed as soon as possible, and no later than 10 years after the Review Conference. In the lead up to this milestone meeting, ICBL is shining the spotlight on some key countries impacted by the scourge of antipersonnel landmines.

In this second spotlight focus, we are presenting Myanmar’s landmine problem and efforts to address it to date.

"My prosthetic is 27 years old now. It is the first one, the only one I received and I have never changed it.”- Myanmar landmine survivor, Asein (47) © Giovanni Diffidenti

Commit to Complete

The ICBL is challenging Myanmar to commit to:

• A moratorium on production and new use of antipersonnel mines.

• Include a specific and unambiguous prohibition on antipersonnel mine use within the nationwide ceasefire.

• Approve national mine action standards and start activities at the Myanmar Mine Action Centre.

• Start a technical survey to determine the extent of mined areas and allow for the safe return of refugees and displaced people.

The origin and impact of the landmine issue in Myanmar

Mine use and production (government and non-state armed groups)

Mine warfare has taken place in Myanmar, or Burma, for almost half a century. Antipersonnel mines were used to a limited extent during WWII, and subsequent to independence in 1947 in armed conflict between the Communist Party of Burma and the Burmese Army. One retired military doctor told ICBL campaigner and Monitor editor Yeshua Moser-Puangsuwan that “when the Burma Army soldiers first encountered antipersonnel mines laid by Communist Party, they thought the enemy was using black magic, as the soldiers were suddenly thrown up in the air by a puff of smoke and a loud noise, we had to explain to them what it was.”

Since the demise of the Communist Party, many ethnic groups within the country raised their own militias during the following decades, and engaged in armed conflict against the central authorities, including mine warfare, until today.

The ICBL has documented extensive use of antipersonnel mines by government forces and by non-state armed groups (NSAG) in many areas of Myanmar/Burma, since the publication of ICBL’s first annual Landmine Monitor report in 1999.

The Defense Products Industries of Myanmar is a state enterprise at Ngyaung Chay Dauk in western Bago regionwhich produces fragmentation, blast, and non-detectable antipersonnel landmines. These include: the MM1, which is modeled on the Chinese Type-59 stake-mounted fragmentation mine; the MM2, which is similar to the Chinese Type-58 blast mine; an undesignated copy of the US M14 plastic mine; and a Claymore-type directional fragmentation mine. Myanmar has imported antipersonnel mines of Chinese, Indian, Italian, Soviet, United States, and unidentified manufacture. Myanmar is not known to have exported antipersonnel mines.

In 1999 Myanmar stated that it supported an export ban on antipersonnel mines, but is not known to have a formal moratorium on export in place. Non-state armed groups in Myanmar have acquired antipersonnel mines by lifting army-laid mines from the ground, seizing army stocks, and from the regional clandestine arms market. Non-state armed groups also self produce blast and fragmentation mines, and some have the capacity to manufacture Claymore-type directional fragmentation mines, antipersonnel mines with antihandlingfuzes, and explosive booby-traps.

Mine Contamination

No one knows the true extent of mine contamination in the country. According to information gathered by the ICBL in the past 15 years, there is some level of antipersonnel landmine contamination in 50 townships, in 10 of Myanmar’s 14 internal divisions, in Kachin, Kayin, Kayah, Mon, Rakhine, and Shan states, as well as in the Bago and Tanintharyi regions. There are also believed to be some mined areas in townships on the Indian border of Chin and Sagaing states. Kayin state and Bago region are suspected to contain the heaviest mine contamination and have the highest number of recorded casualties.

Mines have been laid in a highly dispersed way within the country, due to long running insurgencies. A rice field may have a few mines laid to prohibit one armed group from chasing one which was fleeing, or a few mines may be laid on a mountain trail because one side or the other wanted to prohibit movement of combatants in that area.

Casualties and victim assistance

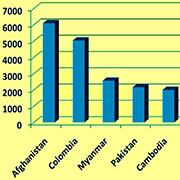

There are no official statistics in Myanmar on how many people are killed or injured by  antipersonnel mines. Since 1999, the ICBL has documented 3,349 antipersonnel mine casualties within the country. When compared to other countries with mine casualties over the past half decade Myanmar has the third highest casualty rate, after Afghanistan and Colombia. Victim assistance, especially for civilians, remains inadequate. Years of war and neglect has meant the country’s civil health system is in an impoverished condition unable to deliver adequate response to most health needs, especially resource intensive ones like landmine injuries. In late 2011, Myanmar acceded to the Convention on the Rights of Disabled People. In the past two years more assistance to mine victims has become available and the number of non-governmental organizations providing services to the mine disabled has increased.

antipersonnel mines. Since 1999, the ICBL has documented 3,349 antipersonnel mine casualties within the country. When compared to other countries with mine casualties over the past half decade Myanmar has the third highest casualty rate, after Afghanistan and Colombia. Victim assistance, especially for civilians, remains inadequate. Years of war and neglect has meant the country’s civil health system is in an impoverished condition unable to deliver adequate response to most health needs, especially resource intensive ones like landmine injuries. In late 2011, Myanmar acceded to the Convention on the Rights of Disabled People. In the past two years more assistance to mine victims has become available and the number of non-governmental organizations providing services to the mine disabled has increased.

MyintMyint (not her real name) became a mine victim in her home township of Hpapun, in Kayin State in 2011. She said “I stepped on a mine on myway to market. I used that path everyday. I had not heard of any military activity in that area, ever. There are not mined areas near my village although I have heard there are near other villages.” Some time later she was found by another villager, who took her to a clinic for treatment which was normally a two hour walk from her village. She returned with a 100,000 kyat bill for the amputation she received, which was money she didn't have.

Mu Che (27) “I lived in Loh Boo village in Hpa-an District, Karen State. When I was 11 years old I stepped on a mine while I was looking after a cow.” © Giovanni Diffidenti

Fortunately for her, her village took up a collection and the bill was paid. Since her injury, she said, “No one in the village dared take that path to market again. They must go by another path which takes much longer.” She does not know if there were any other mines in that area, but work in a plantation near where she stepped on the mine stopped due to fear of mines, and all the workers there lost their jobs. When ICBL’s Yeshua Moser-Puangsuwan met her, she was out of a job.

Myanmar and the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty

In late 2011 the post-military junta regime in power in Myanmar launched a nationwide initiative to bring all armed groups within the country to a peace settlement. Since that time there has been a significant drop in armed conflict throughout the country with the exception of one state in the north, Kachin State. Dialog on the creation of a ceasefire regime and a peace process has been ongoing since that time. To date, at least 13 groups have agreed to take part in peace discussions, however, as of February 2014, no nationwide comprehensive ceasefire protocol had been signed.

After the launching of the government initiated discussions on peace, in early 2012, the President requested assistance with mine clearance from some visiting European delegations, and the government then designated the coordination of mine action activities to be placed within the governments focal point for peace dialog facilitation, the Myanmar Peace Centre. Although the President, who is a former military officer and member of the former military junta, has played a key role in promoting a peace process and bringing mine action actors into the country, he has not appeared to have embraced the landmine ban. In November 2012, Myanmar’s President TheinSein stated at the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) summit, “Myanmar has not signed Ottawa Convention yet. But, Myanmar always opposes the excessive use of land mines. Meanwhile, I believe that for defence purpose, we need to use landmines in order to safeguard the life and property of people and self-defence.”

Myanmar first publicly admitted the existence of a landmine problem within the country in early 2012. Since 2011, Myanmar has regularly sent an observer delegate to States Parties Meetings of the Mine Ban Treaty. In December 2013, at the 13th Meeting of States Parties the delegate of Myanmar stated that Myanmar was paying “attention to the Convention” and that their presence as observers “clearly reflects our keen interest in the present and future work of the convention.”

In May 2013, Member of Parliament and Nobel Peace Laureate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, speaking on disability in Myanmar, said: “Landmines are the hardcore of the peace and reconciliation process in our country. People with disabilities are constantly increasing in number due to the existence of landmines… I truly desire the recovery of the people who are injured, by any means: those who are physically or mentally struggling in life.”

speaking on disability in Myanmar, said: “Landmines are the hardcore of the peace and reconciliation process in our country. People with disabilities are constantly increasing in number due to the existence of landmines… I truly desire the recovery of the people who are injured, by any means: those who are physically or mentally struggling in life.”

In January 2013, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi visited what is believed to be one of the most heavily mine-impacted communities in the country, Mone in Kyaukkyi Township, to learn about the situation of mine victims. In February 2013 she organized a briefing on the landmine issue by the ICBL in Naypyitaw on the landmine ban, for medical doctors who were Members of Parliament, and in May 2013 the ICBL was able to send its first high level delegation to the country to discuss the mine ban with the current government.

ICBL/MCBL Delegation meets with President's Minister U Aung Min in Naypyitaw, May 2013. ICBL delegation comprised of Amb. Satnam Jit Singh (left, center), Monitor Research Editor Yeshua Moser-Puangsuwan (left, fore) and U Myat Oo, Myanmar CBL Chair (left, rear) ©ICBL

The establishment and role of civil society in Myanmar

Myanmar civil society has started to organize themselves in relation to the landmine issue. Seven local NGOs, led by the Myammar Physically Handicapped Association (MPHA), formed the Myanmar Campaign to Ban Landmines (CBL). MyatOo, the MPHA chairman said his reason for helping for the MCBL was that while he could accept that some people were disabled from birth, like himself, he could not accept that some people could become disabled by the conscious actions of others. For him, banning landmines was a prevention of disability issue.

In December 2013, the country's first local demining organization registered as an NGO. The founding director is a former soldier who laid mines, and lost his leg to one of them. In a January 2014 interview, he shared the following comments.

“I had worked in the Myanmar Army since 1967 and in 1990 I lost my leg by the landmine. Before I was injured by the landmine I had many experiences in the Army. We had to fight the ethnic enemy and mainly the Burmese Communist Party, and in that battle we used a lot of the landmine, on our side and on the ethnic armed forces side.

Every group used the landmine. So at that time I didn't consider deeply that this landmine might be very bad. I never thought about this. When I was injured I had to retire from the Army, and after that I could consider what I have done, and what I have to do now for the people. I owe to the people because I learned that some civilians died or were injured by our landmines. So I am so sorry for that. So I owe something to them. So now I am a civilian also, and I am retired so I want to do demining, I want to remove all the mines I placed in the frontier line. And also I want to persuade other former combatants to do this with me, together.”

Every group used the landmine. So at that time I didn't consider deeply that this landmine might be very bad. I never thought about this. When I was injured I had to retire from the Army, and after that I could consider what I have done, and what I have to do now for the people. I owe to the people because I learned that some civilians died or were injured by our landmines. So I am so sorry for that. So I owe something to them. So now I am a civilian also, and I am retired so I want to do demining, I want to remove all the mines I placed in the frontier line. And also I want to persuade other former combatants to do this with me, together.”

Thant Zin, founder of Peace Myanmar Aid foundation,the first and only local NGO registered to undertake mine clearance. ©ICBL

WHAT MYANMAR SHOULD DO NOW

Mine use and production (government and non-state armed groups)

The ICBL delegation which met with government authorities in May 2013 encouraged that Myanmar should enact a moratorium on any new use of antipersonnel mines. It is the ICBL’s opinion that this will be supportive of the efforts to obtain a nationwide ceasefire and a confidence building measure for the ongoing peace dialog. In tandem with this, a moratorium on further production of antipersonnel mines should also be implemented, since there would be no need to produce if none were being used.

The ICBL has encouraged non-state armed groups to announce a unilateral halt on further use of antipersonnel mines during the period of dialog and negotiations as a confidence building measure.

Mine Clearance and Mine Risk Education

The government should approve the draft Myanmar Mine Action Standards which both Ministry and NGO agencies developed in 2013. The Myanmar Mine Action Centre, inaugurated by the government in 2012, remains without staff and inactive. A budget should be designated for this entity, and a staff hired and trained so that it can undertake promised coordination of mine action activities. Technical survey of mined areas should be commenced at the soonest possible opportunity so that mined areas can be identified and scheduled for clearance.

Victim Assistance

The ICBL congratulates the government of Myanmar for joining the Convention on the Rights of Disabled People and has taken note that there has been some welcome increase in access to assistance for victims of antipersonnel mines in the past two years. We encourage the near term completion of its national implementation legislation for the CRDP. The ICBL would strongly encourage the government to establish a mine victim assistance coordination mechanism and include mine survivors in victim assistance planning.

***************************************************************************

Additional resources:

- United Nations Myanmar Information Management Unit (UN MIMU) Mine Action page

- Mine Free Myanmar (formerly Halt Mine Use in Myanmar/Burma):

- Monitor Country Reports on Myanmar/Burma since 1999 in Burmese and English

- Statements by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, Thura U Tin Oo, Dr. Cynthia Maung, Ko Bo Kyi on the Landmine Ban

- Geneva Call Video Invisible Enemies Responding to the landmine threat in Burma/Myanmar (English subtitles)

- ICBL: Myanmar FAQ

- Photo exhibition of Burmese landmine survivors, by Giovanni Diffidenti